HOUSING NEEDS ASSESSMENT

Table Of Contents

Executive Summary

The Nibinamik First Nation Housing Needs Assessment moves beyond measuring housing as only physical shelter towards recognition of housing’s role in sustaining individual and community wellness.

In acknowledging the relationship between housing and occupant well-being, definitions of need are expanded to include physical, social and psychological elements. Measuring these elements with the specificity required to capture the experience of Nibinamik community members necessitated the creation of unique metrics, rooting need in local values, goals and aspirations. The findings of this report collected through a survey, community workshops and sharing circles- provide community leaders and housing staff with high quality information, documenting the current lived experience of community members and their goals for the future of housing.

Rather than following a strictly deficiency-based model recording only need, the Nibinamik First Nation Needs Assessment sought and recorded community solutions. For too long, Nibinamik, as well

as other First Nations across the country, have been studied, their inequitable outcomes recorded, with little action taken. While communities have developed and advocated for community-created solutions to housing to address well-documented deficiencies, government actors and policy-makers impose solutions on First Nations. This continues colonial cycles of intervention, underfunding and inequity.

Colonial intervention in Nibinamik’s housing has created the existing community form and housing structures- both of which have been found to be inappropriate. Breaking these cycles, rather than contributing to them, is the foundation of the survey tool and the discussion presented in this report. Community members were encouraged to reimagine housing as a symbol of their own values. The commitment of Nibinamik First Nation leadership and housing staff to engage community members throughout the housing system- including design, governance and management- has begun the process of creating self-determination in the housing system.

Introduction

Housing in First Nations communities continues to be inadequate and of substandard quality, contributing to poor health, education and social outcomes. Nibinamik’s Housing Needs Assessment was undertaken by community leaders, housing staff and membership who believed that their housing outcomes were inequitable. Through this project, high quality, local, context-specific data was recorded profiling the existing state of housing, its impact on families and changes required for the well-being of future generations.

While many housing needs assessments rely strictly on Core Housing Need- the existing Canadian metric of housing need- it has consistently been found to be inappropriate for on-reserve housing.1 Community leaders in Nibinamik, as part of a wider strategy addressing community wellness, sought a more holistic measure of housing, focusing on members’ experiences and relationships with their homes. Rooted in community members’ experiences the Nibinamik Housing Needs Assessment develops a unique, place- based, framework measuring occupant satisfaction with housing and community development.

Beyond recording existing conditions, the Nibinamik Housing Needs Assessment engaged community members in creating alternatives to their existing housing system. The aspirations, experiences and knowledge shared by community members young and old, and represented throughout this report, can guide community leaders and housing staff in decision making. Undertaken simultaneously with changes to housing governance Nibinamik looked to re-establish its housing system entirely, focusing on self- determination. Discussion focused on existing strengths, planning for a housing system independent from outside intervention and creating innovative solutions.

Section 2 of this report provides the purpose and objectives that guided this research and findings. Section 3 examines needs assessments and the deficiencies with the current evaluation model, looking instead to how housing evaluation can foster wellness. Section 4 reviews the context relevant to the discussion of housing in Nibinamik including a detailed demographic profile. Section 5 provides the methods used to develop the needs assessment survey as well analyze the findings. Section 6 presents and explores the implications of the needs assessment survey findings. Section 7 reviews the existing housing stock and combined with the findings, assesses the current and future housing needs. Section 8 provides recommendations to enable the implementation of findings that will move housing towards a place of wellness in Nibinamik First Nation.

Goals, Timeline + Milestones

The overarching objective of Nibinamik’s Housing Needs Assessment is to assist community leadership in understanding Nibinamik’s housing need, its impact on community members and recording potential community-driven solutions. Four connected project goals were set in order to achieve this objective:

- Document Existing Housing Conditions

Create a survey tool reflective of local values which documents existing housing conditions and their effect on community members.

2. Identify Priority Action Areas

Use survey and workshop findings to identify areas of the housing system most in need of change and which can have the greatest impact on community well- being.

3. Reimagine Design through Community Engagement

Through immersive, mixed-media workshops engage community members in visioning alternative solutions to housing and community design which more appropriately meet Nibinamik’s climate, geography and culture.

4. Create Community-Driven Housing Action Plans

Integrating community visioning with identified need, action plans look to embed community member values in the solution to housing need.

Regional Context

The Community

“In April of 1975, the Nibinamik people, the Summer Beaver people, decided to move back to the Summer Beaver area, and solidly re-establish our community and way of life. Spring break-up came around May 16 or 20 in 1975 and we started to organize and pack our gear for the long trip to Summer Beaver and a new lease on life”2

Nibinamik is a community of nearly 400 members. It is a community accessible only by air and winter ice road, and lies 500 kilometers northeast of Thunder Bay.

History of Housing in Nibinamik

Nibinamik, as it exists today, was formed in the summer of 1975 by a number of families who left Lansdowne House in search of a better life. That summer, as more and more families completed the canoe journey from Lansdowne House to Nibinamik, “people became buoyed with the hope and dreams of once again being in control of and responsible for all aspects of their lives”.3 In the first community meeting, held in a large tent with the nearly 100 community members having returned to the Summer Beaver area, it was decided that all structures would be built of logs. Logs would allow for an equilibrium to be maintained with the natural environment while maximizing local resources and would also help to ensure independence from government programs. The first summer in Nibinamik 17 homes were constructed.

Cooperative, community-led building would continue in Nibinamik over the coming decades expanding the number of homes to meet the growing population. As community capacity in building homes grew, a unique style of log home developed in Nibinamik, characterized by vertical logs, corner decoration and red painted ends.

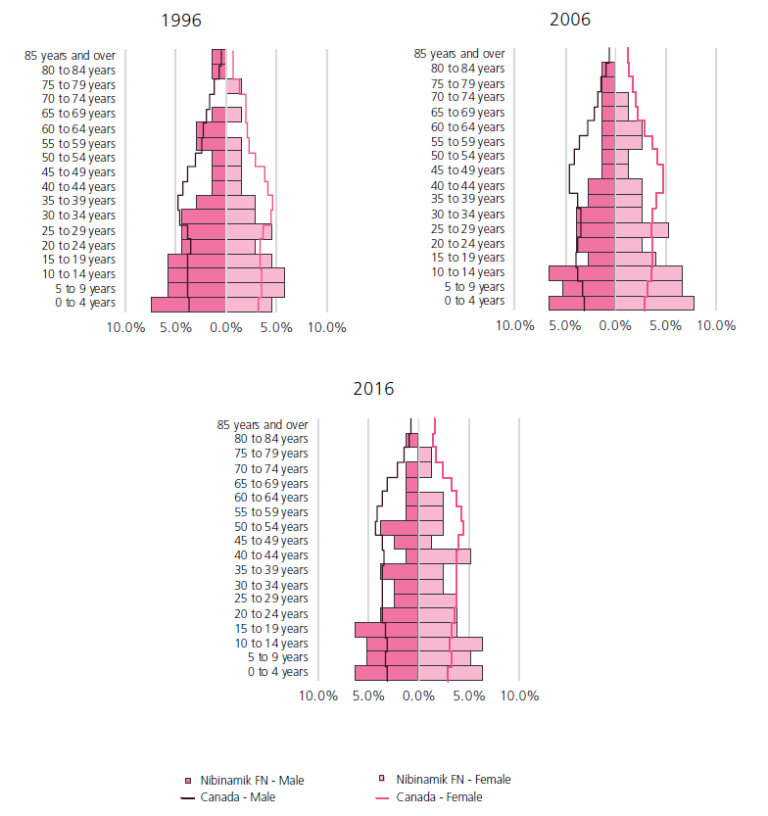

Nibinamik is a young community, with 58 percent of its population under the age of 30.4 The population pyramids show a tapering of age cohorts, with only 10 percent of community members 60 years of age or over. The growth rate in the community is low, at only 1 percent. This low growth may be a result of community members leaving the community for economic opportunities, access to healthcare, or schooling.

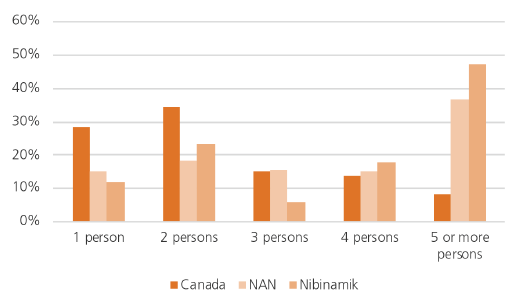

The average household size in Nibinamik is 4.2 persons – nearly twice the size of the national average of 2.4 persons per private household. 47 percent of households in the community are 5 or more persons compared to 8.4 percent in Canada. Despite having a high proportion of 5 or more persons only 30 percent of housing is 4 or more bedrooms.

Current Housing in Nibinamik

Forward momentum in community-directed housing came to an abrupt end in the 1990s when forest fires made it impossible for community members to access sufficient materials to support log building. For the first time, government housing programs and southern-style housing- similar to those being developed on-reserve across the region- was introduced in Nibinamik. Government housing was developed primarily in a new subdivision Six Nations using a cul-de-sac model. Financial difficulties, and third-party management ended this new form of housing growth and have greatly reduced recent housing expenditure.

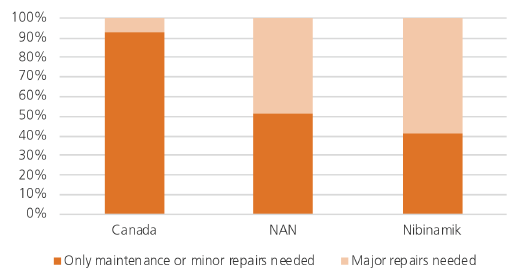

Currently, there are 93 homes in Nibinamik. 56 percent of housing is in need of major repair and renovation.

Currently, two additional homes are undergoing major renovations to make them habitable once again and six new units are being built. Six serviced lots area are available for development and there remain unbuilt areas within the community boundary that may be suitable for future development though the ground is unsuitable in most areas. Beyond the existing boundary the community is bounded by Nibinamik Lake on the North, East and West and the esker to the South and East.

What is Needs Assessment?

Housing need, throughout this project looks to address four concerns: existing need, growth related need, deterioration-related need and migration need. The methodology presented throughout moves beyond a standard Canadian conceptualization of housing need and towards a community-developed understanding of need, rooted in the local context.

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) assesses need through hybrid metric Core Housing Need: affordability, adequacy, suitability.5 In the context of fly-in reserve housing, where markets are often not present, adequacy and suitability are the only relevant criterion used to identify households living below minimum acceptable standards.6

Adequacy refers to the condition of the housing itself and is based on functioning basic services. This criterion asks: is the house in need of major repair?; do the services of a housing unit function? Suitability refers to the unit size and whether or not the housing unit is an acceptable size- without overcrowding- for the makeup of residents. Overcrowding is based on the National Occupancy Standard (NOS) however, the current national density average, used as a benchmark in this report is 2.4 people per house.7

Core Housing Need is currently utilized as a measure of housing by the federal government, provincial housing agencies, municipalities and non-profit organizations. Therefore, this model continues to be applied on-reserve, despite its limitations. By relying on these standards to define housing need, only the physical condition of individual housing units is captured. Core Housing Need fails to understand the relationship between the priorities, preferences and experience of housing occupants and poor housing outcomes.

Housing is not a single unit in isolation, rather, housing exists within and is connected to social, cultural, and natural environments.8,9,10 Rather than utilize an externally imposed definition for adequate housing of which to measure against and aspire to, this project assesses and defines housing need in Nibinamik based on community-identified needs, priorities and values.

The survey conducts a local housing needs assessment via five interrelated aspects of housing:

- Demographics and occupancy;

- Design and preferences;

- Existing physical condtions;

- Perceptions of housing and well-being impacts; and

- Community layout and design.

Housing and Wellness

Concurrent with the housing needs assessment Nibinamik created the Nibinamik Community Wellness Index (hereafter: Wellness Index Project). The Wellness Index Project was an immersive process through which community members identified their priorities, goals, action plans and metrics for creating well- being in the community. Importantly, this project recognized the interconnectedness of issues across the ten areas identified as impacting well-being: children, family & community; economic development; education; food security; health; housing; infrastructure; land, language & culture; sports & recreation; and youth.

Housing’s place in the Wellness Index Project again confirms that houses are more than physical places of shelter, but are critical to the social and psychological well-being of both individuals and community.11 Housing satisfies physical needs by providing shelter, “psychological needs by providing a sense of personal space and privacy… [and] social needs by providing a gathering area and communal space for the family”.12 Housing is a community asset- and right- required to achieve well-being

The personal nature of housing means that one-size-fits-all approaches are often misaligned to local understandings. External interventions and policy priorities have failed to solve Nibinamik’s ongoing housing crisis. Strategies for long-term community growth and community wellness are framed here through the priorities and values identified by community members. These learnings and strategies- rooted in local context- have the potential to establish a new, appropriate housing system. However, implementation and success can only be achieved if this system is supported by all community partners.

Methodology

The Nibinamik Housing Needs Assessment was a collaborative and immersive process. It engaged Nibinamik First Nation membership in a critical evaluation of their living environments and in a process of solution-oriented community planning. Continuing a longstanding partnership, together design lab at Ryerson University, +city lab, community leaders, housing staff and community facilitators created distinct, locally-based tools to accomplish project goals. A simple framework guided all community engagement: listen, learn and share which recognizes that each community member, regardless of age, gender or level of education, brings their own unique set of experiences, knowledge and perspective to housing discussions. Individual uniqueness implies that each individual deserves a voice and that we can all learn from one another if we take the time to listen. Sharing, as is being done in this report, acknowledges the lived experiences of community members, which ought to be acted upon and that no voice should be silenced.

Two distinct sets of tools were used to record the information found in forming this report: surveys and workshops. Surveys were developed with community leaders and housing staff as a means of beginning individual conversations and assessments of living environments through which high quality data could be captured. The survey itself changed slightly through the project’s duration to reflect issues with initial questions, and to a growing desire for more information (detailed changes are described in Appendix A: Methodology). Surveys were conducted by housing staff, community facilitators, together design lab and +city lab beginning October 2016 through February 2018 during both individual home visits or

during community events. These were personal conversations, encouraging occupants to reflect on their relationships with their living environment and the future of their community and conversation often extended beyond the bounds of questions asked. Reflections of community members were recorded and help to form the findings and discussion found within the report. In many cases, these conversations were the first time that community members had been given a platform from which to critically reflect on their housing’s appropriateness and its role their family’s well-being.

Workshops complimented surveying by providing an opportunity for community members to interactively create solutions to the problems they had identified. Specific workshops focused on: community growth and planning, housing design, and housing governance. Specific activities were designed to engage different community demographics with a particular focus on involving children and youth in the discussion. The experiential nature of workshops allowed for collaboration between community members and the development of an iterative process allowing for the testing and retesting of ideas. The learnings gained from workshops are foundational to project findings and recommendations and help to guide decision making for housing in Nibinamik.

Housing Now

Profile of Housing in Nibinamik

Physical

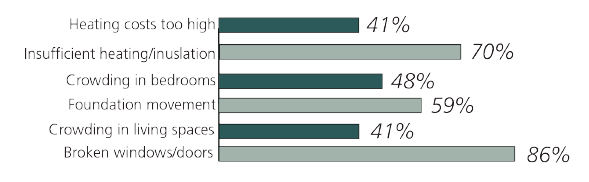

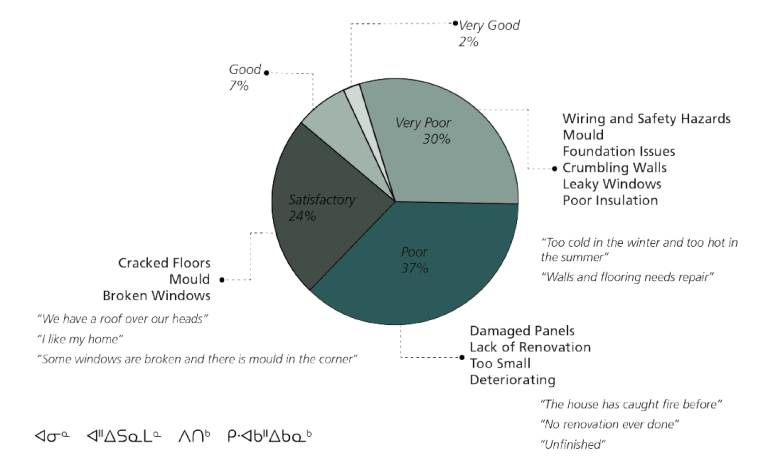

Any assessment of housing must include a review of the physical structures which currently house community members. 93 band-owned and operated houses are currently present within the community and are divided amongst two distinct sections of town. The majority of structures are single-storey log-houses with newer homes using stick-frame construction with either a basement or crawl space. In advance of data collection, community members, leaders and housing staff identified a number of problems which they believed to be pervasive across Nibinamik: insufficient heating and insulation, broken windows and doors, mould growth and inadequate foundation systems. These were explored at the level of individual home, while also identifying other physical problems.

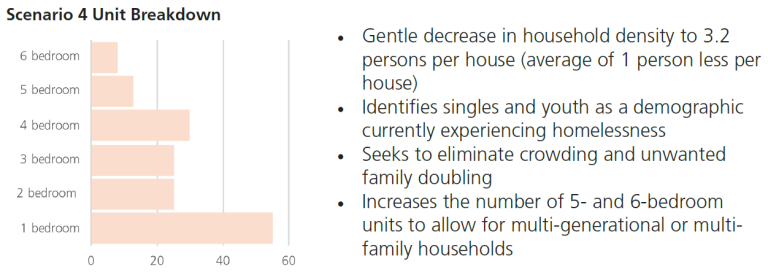

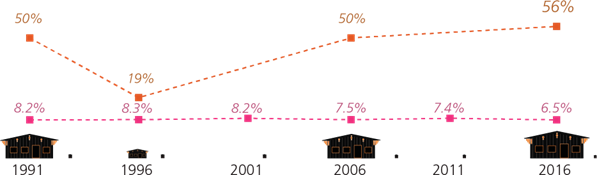

In particular, while many studies of housing need across fly-in First Nations point to common trends resulting from the standardization of units13, here we look to discover whether unique conditions exist resulting from the Nibinamik’s specific housing history. All community-identified issues should be understood within a context of great, and growing inequality. Adequacy the comparative indicator used in Canada to measure physical condition of housing showed in 2016 houses that housing in Nibinamik was 8.6 times more likely to be in need of major repair than the national average.14 Since 2001 the percentage of homes in need of major repair nationally has decreased from 8.2 percent to 6.5 percent whereas in Nibinamik the number has from grown to 56 percent.15,16 Community-identified physical issues serve not to demonstrate the poor condition of housing in Nibinamik- this is already well understood- but instead help create a set of priorities in addressing need.

To explore the physical condition of housing the report examines:

1. Community-identified issues; and

2. Structural profile of homes.

Community-identified Issues

Community members were asked to identify the most pressing physical issues within their house. This helps to build a greater understanding of the condition of community housing and the pervasive issues that exist. Several issues were identified, including: broken windows and doors, plumbing and water issues, as well as foundation shifting.

Renovation Program

In Nibinamik a majority of the houses are constructed of logs. This type of house construction is unique within Nishnawbe Aski Territory. Therefore, given the limited use of log construction special expertise and materials are required. While this expertise traditionally existed within the community- with many having been trained in carpentry and renovation- this capacity is being lost. Both community training and access to materials for log construction had ceased in the early 1990s after forest fires. More than twenty years later, many of these log houses have had little work completed and have fallen into disrepair.

While capacity and material shortages are one cause of a growing backlog of repairs, so too are funding gaps. Recognition exists that federal funding programs are insufficient to “properly manage and maintain housing and infrastructure on reserve” leading to an ever-increasing backlog of need.17 The existing shortfall is particularly problematic for fly-in communities, like Nibinamik, where local markets and other funding sources are minimal. Although it has been recorded that fly-in communities receive additional funding through a remote and isolation index multiplier, this amount has not kept pace with increasing costs of materials and transport. 18

The reliance on winter roads for transporting materials to reduce cost places significant burden on Nibinamik to store goods through the winter into the building season. Nibinamik does not have warehousing or storage facilities, and as a result frequently experiences significant material losses occur each winter.

Windows and Doors

Physical issues with the houses do exist and have been clearly articulated by community members. The top issue identified by community members was broken windows and doors. Although this is considered a minor repair, there are wider reaching implications. First, without the funding and capacity to maintain a supply of windows- as discussed previously- houses cannot be quickly repaired, leaving community members in drafty and cold houses throughout the winter months. To continually ship materials in by air is cost prohibitive and access by road is limited to a short span of time in the winter. Second, broken windows and doors are often a result of structural issues. Foundation shifting causes windows to crack which allows moisture into the structure of the house, leading to mould growth. Therefore, preventing broken windows- often a result of climate and geographic inappropriateness in house design and construction- may prevent other, more severe issues in the house.

Structural Profile

Connection to Culture and Landscape

When assessing existing metrics, attention must be given to both the interior private space and also the semi-public and public spaces around the house.19 These spaces shape an occupants’ experience with, and understanding of, their home. When housing and community spaces are designed by their users they represent their culture and lifestyle, matching how occupants imagine their community.20 In Nibinamik, the connection to natural features demonstrates the symbolic meaning of housing as cultural markers.

The layout of Old Town demonstrates integration of the land and water into the housing plan. The natural landscape- including the bush, trees, and hills- has been maintained with the houses arranged to blend organically with the environment. This is contrasted with the cul-de-sac model of Six Nations; suburban grid housing plans often require the landscape to conform to the housing model rather than integrate with the natural environment. While the survey showed that community members prefer the distance between houses in Six Nations, fewer homes maintain natural features and residents of Six Nations put a higher level of importance on natural features. This change in importance is likely explained through a perception gap- a disconnection from natural features reveals and raises their importance.

Future housing in Nibinamik- meeting the need outlined in this report- must consider housing’s important symbolic role in the community. Connection to natural features and development of secondary structures is critical to the preservation of lifestyle and cultural practices. These elements, outside of the private interior spaces of homes are what form the bond between occupants, housing and environment, and create place-based rootedness central to occupant satisfaction.

More Varied Housing Mix

In addition to the contrast in layout and connection to culture between Six Nations and Old Town, the housing mix is also different. While we see a more equal split of 2-, 3- and 4- bedroom units with some 1-, 5- and 6- bedroom units in Old Town, Six Nations demonstrates a more standardized approach with 72% of units being 3- and 4-bedroom. This more standardized approach is common of government funded reserve housing across Northern Ontario. However, these houses do not effectively serve community members across all life stages which can contribute to problems of crowding and safety, explored later in the report. The shift in housing mix, occurring as a result in shifting from self- determined housing plans to housing developed from within government programming demonstrates its inappropriateness.

Perceptions of the House

Physical elements of evaluation reduce the house to only its most simplest function; the house as shelter.21 A house is the focal point from which daily life centers; houses are more than a physical structure but are a reflection of culture, environment, and values.22 This survey sought to capture the personal-environmental relationships between housing occupants and their home. Houses that match self-image and personal preferences result in more positive well-being outcomes and psychological wellness due to the housing occupant having the ability to exert control over their home environment.

Challenging the notion that there is one ideal house suited to everyone, the survey created an occupant- based framework for housing assessment. Community members each brought their unique set of values and experiences to a discussion of housing. Recording these distinct values allows for a community understanding of appropriate solutions to existing housing need. By focusing on the occupant, rather than the physical structure, self-determination in housing can be realized; developing occupant-derived solutions allows for a sense of rootedness and pride of place.

To explore the physical condition of housing the report examines:

1. Conditions of Houses;

2. Materiality and Tradition;

3. Design; and

4. Well-being.

Conditions of Houses

Expectations

Community members identified a strong dissatisfaction with both the interior and exterior condition of their homes. However, the feedback given in discussion suggests a deeper, more systemic dissatisfaction with community housing beyond the physical conditions. Perceptions of housing conditions are contextual and dynamic. Housing satisfaction, or dissatisfaction, can be understood as a measure of the gap between expectation and lived experience.23,24 Expectations, and therefore perceptions of a given house, are dependent on lived experience and can change through an individual’s life journey.25 For this reason the survey conducted here is complemented by targeted conversations, activities and sharing with community members across demographics. What was learned, is that from a very young age there is a conceptualization of what on-reserve housing or “rez houses” can be.

With conditions consistently deteriorating over the last three decades expectations of housing have shifted. Houses that were once a source of pride, when they were new and functioning, are now falling apart. The positive feelings once associated with logs have in many cases been replaced; feelings of nostalgia and associations with tradition have- for many- been replaced by associations with poverty and sickness. Many current occupants were not part of the community building projects which developed the log homes, nor were they engaged in the design or development of homes in Six Nations. A sense of ownership has clearly been lost from existing housing, and while some claim tradition is important, others look to move on. As connection to housing has decreased, and housing itself deteriorated, community expectation in housing has changed. Persistent physical need and negative perceptions of

on-reserve housing has created frustration and apathy with the housing system. Establishing local control over the housing system, and rooting the system in local values, housing in can become a community symbol of pride and representative of this unique place.

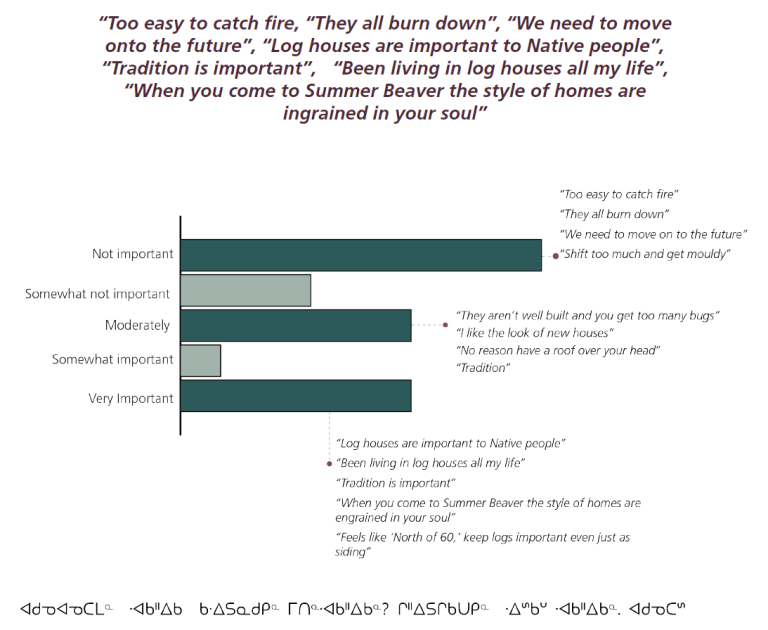

Materiality and Tradition

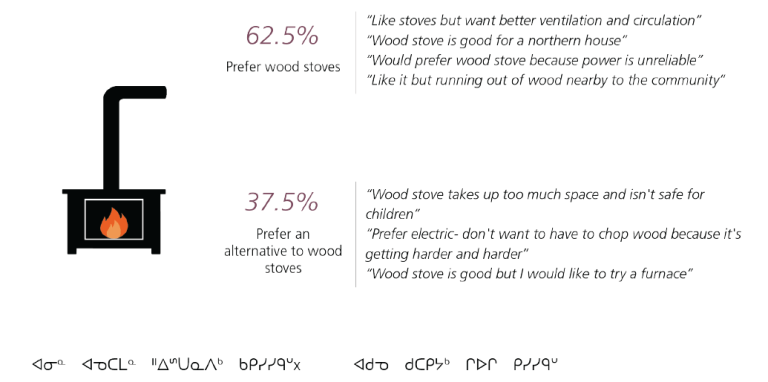

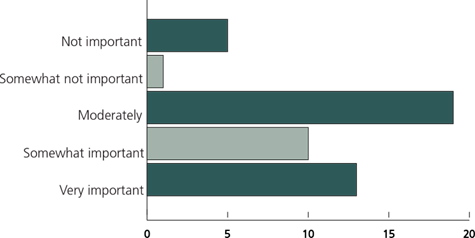

Critical to the shifting perceptions of housing in Nibinamik are relationships to materials. Log homes heated with wood stoves are part of the history of Nibinamik, as one community member expressed, “when you come to Summer Beaver the style of homes are ingrained in your soul”. Tension exists however, between continuing to develop housing in this way, or instead as another community member suggested a “need to move onto the future”. 36 percent of occupants expressed that wood housing was not at all important to them, while only 23 percent described it as very important.

A common fear associated with both wood stoves and log homes is the potential for fire. Recent house fires, particularly in houses with young children, has many community members looking to alternatives. As one community member expressed, their opposition to log homes is that, “they all burn down” while another expressed log homes are, “too easy to catch fire”.

When considering the development of culturally appropriate housing for Nibinamik it is important to remember this duality of positions. Appropriateness can change and evolve and should not be exclusively linked to one conceptualization of housing. Workshops explored different building materials and styles to consider how traditions may be represented differently.

Negotiating the desire to maintain traditions, a need for increased fire safety and a push for newer housing styles within the community is critical to the future of housing in Nibinamik. There is not, as there was in 1976, one material favoured by all community members and as such there should not be one standard design created for all. The differing needs and values of community members can all be represented by a diverse housing system. Matching housing to lifestyle in Nibinamik is not solely performed by logs, but maintaining the symbolic nature of housing in Nibinamik remains important to many.

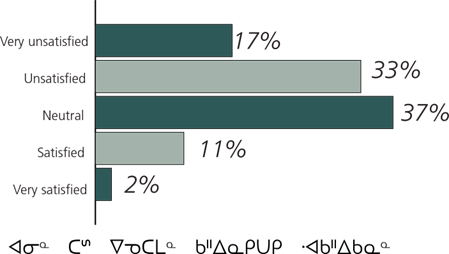

Design

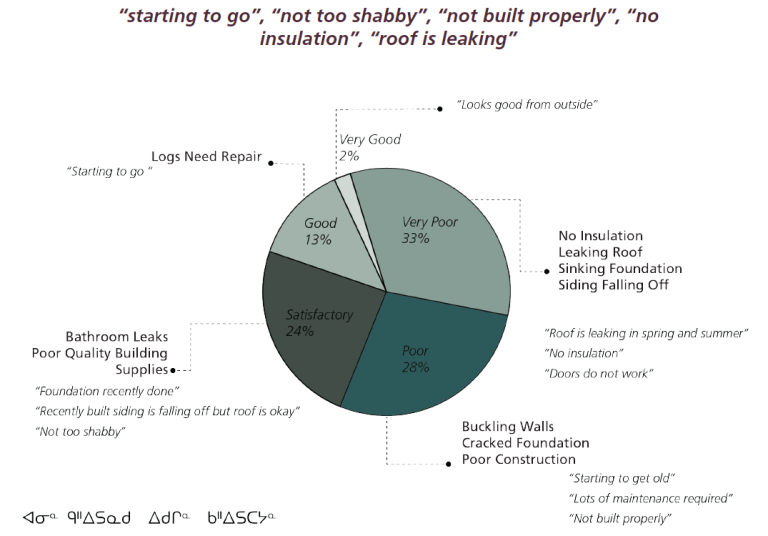

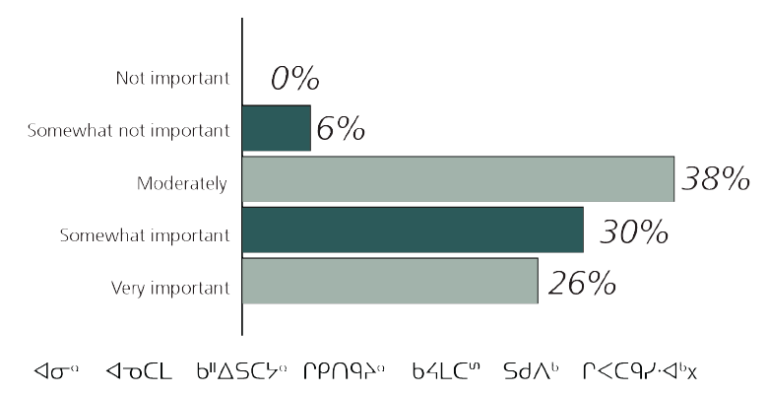

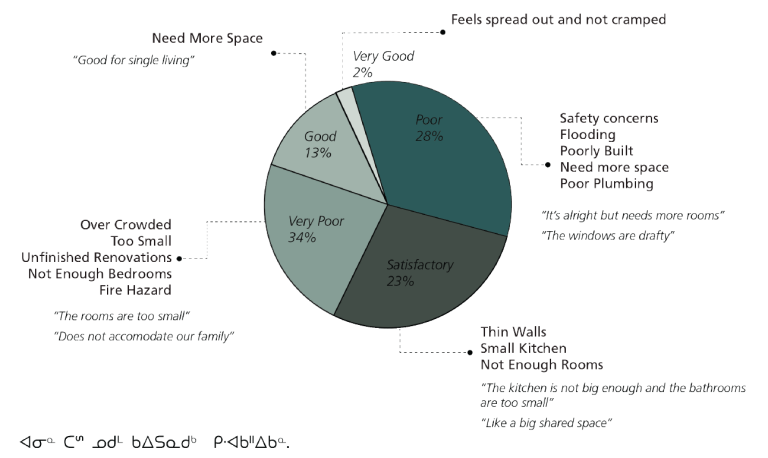

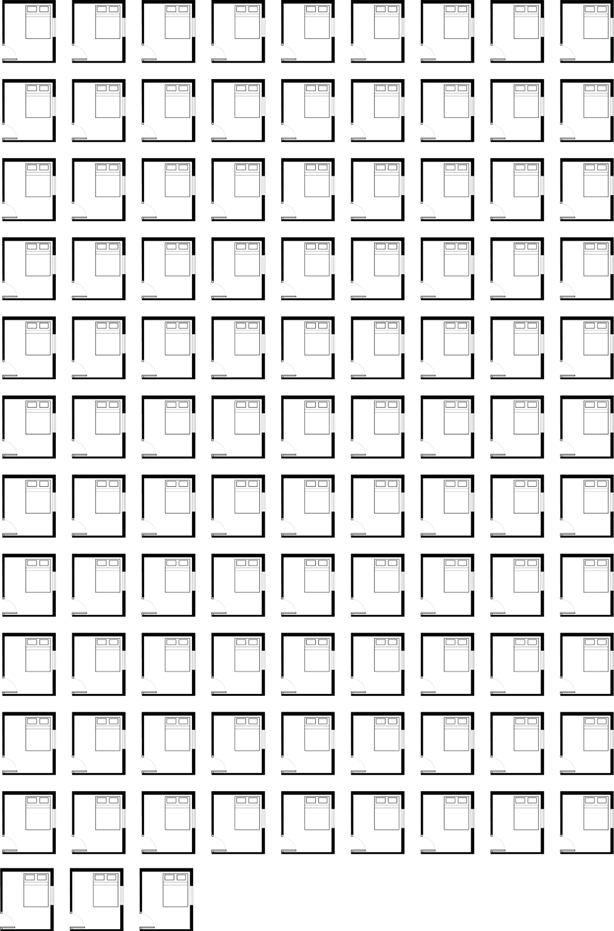

Design is an important framework through which to understand community member satisfaction with housing. The purpose of housing design is to create spaces which meet the needs and values of those for whom it was created.26 While the houses in Old Town were designed and constructed by the community, preferences may change over time and across generations. Occupants now living in those houses were likely not involved in their construction or design thereby resulting in the loss of sense of ownership and control once present. 34 percent of community members rated the design of their house as very poor whereas only 2 percent rated the design as very good (See figure 18). Many of the comments associated with this response point to a desire for larger, shared spaces within the home, houses which can accommodate entire families, and houses designed for specific life stages.

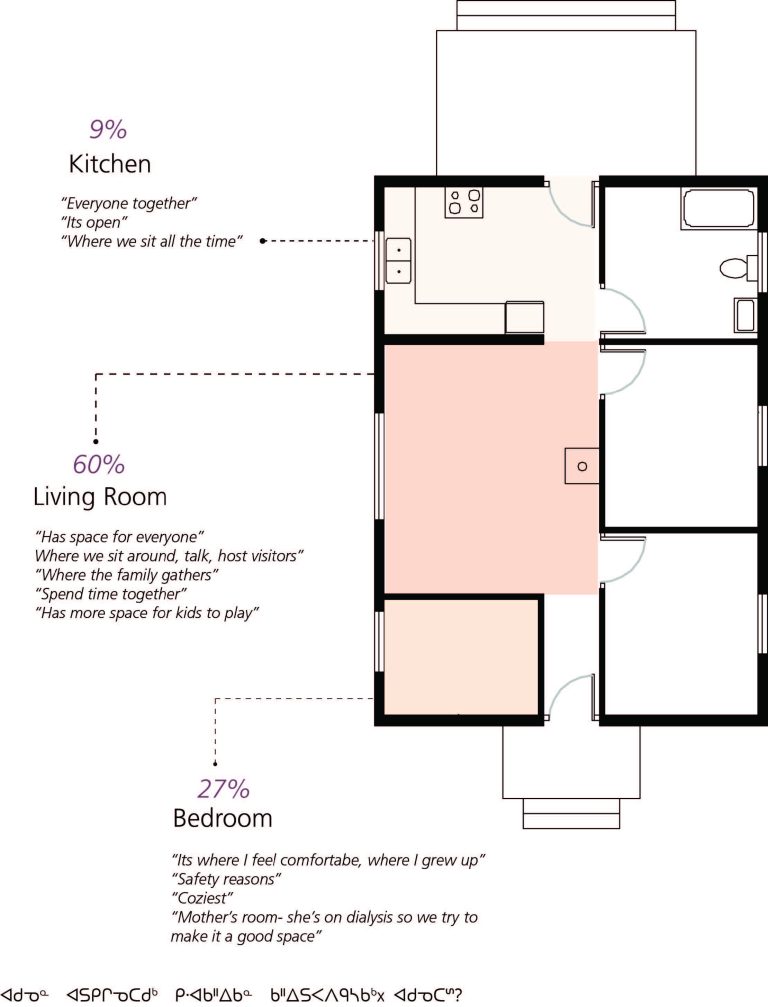

Complementing this, the living room was identified by community members as the most important room in their house (Figure 19). It became clear that housing models are preferred which focus on shared, central spaces. Spaces within which family activities can be shared, and community members across generations can be together.

In the community there is an even proportion of 2-, 3-, and 4-bedroom houses. While this mix may offer houses large enough to accommodate a nuclear family, this presents limited options for housing appropriate for multi-generational families living in one household as well as more than one family living together. It also limits the potential for community youth or singles to have their own spaces.

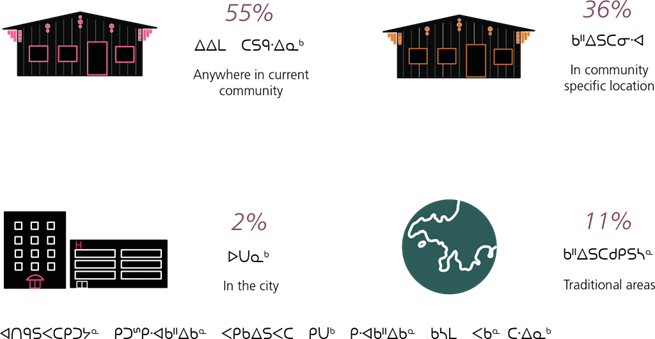

55 percent of community members expressed that they want youth to have the choice whether they live in community or in the city, and a further 36 percent expressed a desire that youth return home to live permanently in Nibinamik. Developing a greater diversity of housing options, including 1- or 5+ bedroom units in the community, would create new places for youth and large families to live safely.

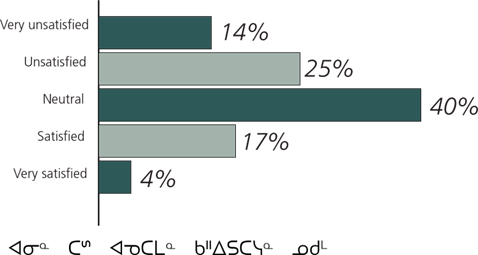

Well-Being

The impact of housing on individual and community wellness is interrelated with many other factors and cannot be measured directly. However, a number of indirect measures were used to demonstrate housing’s role in well-being. Through the Wellness Index Project, the community’s top housing priority was identified as ending crowding and unwanted family doubling- both of which are measured in this report. In addition, overall housing satisfaction, perception of safety and interior and exterior condition of homes are also measured as proxies for well-being. Each of these metrics are understood as relational measures dependent of the experiences and expectations of an individual. Together, these metrics begin to represent housing systems’ complex relationship with well-being.

Crowding

Crowding is most often defined as a physical calculation- the house is deemed suitable if it has enough bedrooms for the size and composition of the household27– with physical impacts- such as increased risk of infectious illnesses.28 However, the causes and impacts of crowding are further reaching, rooted in psycho-social environmental relationships. For example, crowding increases potential of stress, violence, and suicide, all of which can be felt by community members living in diversity of a housing situations.29

Beyond a physical calculation, crowding can also be perceived differently by members living in the same household. The perception of crowding can occur whenever an individual is not able to successfully prevent undesired interactions through space, territory, verbal and nonverbal behaviours.30 Crowding is a result of an individual occupant not having sufficient control over their house to adapt space to meet their needs. Importantly, survey findings reinforce the relational nature of crowding; community members living in the same house do not necessarily identify identical perceptions of crowding.

This report relies on self-assessment of crowding rather than National Occupancy Standard. Self- assessment better represents the definition of crowding presented above; measuring individual relationships to their living environments. In Nibinamik 20 percent of households surveyed had a variation between perception of crowding and National Occupancy Standard. Mismatch between NOS crowding and self-reported crowding indicates that alternative solutions are required to solve the problem.

To address crowding in Nibinamik there is a need for both more and larger units. Community members identified that an additional 102 bedrooms would need to be added to the existing overall community bedroom count to address crowding. Further, of community members who reported more than one family living in their house and wished to live separately, an additional 87 houses are needed to eliminate family doubling and provide space for youth to move out of their family homes. Community members recognized that only together could these changes provide sufficient control of living environments for all to address crowding within the community.

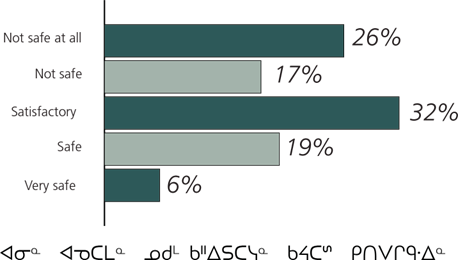

Safety

As with crowding, community members’ perception of housing safety is relational. Safety can refer to physical safety (community member descriptions include: fire safety, electrical, structural issues) and social safety (belonging, protection from violence, emotional and verbal abuse, addiction). Similar to crowding, feelings of safety vary amongst members in the same household, often linked to the ability to assert control over one’s home environment. As seen above with crowding, perceptions of safety can at times be connected to demographic groups. Many young singles- who were found above to not have specific control of their housing- may be causing safety concerns for others in the house. Social breakdown and conflict are described both between houses and within houses as a result of individuals not having spaces over which they feel sufficient control. 26 percent of community members expressed feeling very unsafe in their homes while only 6 percent felt very safe- this maladaptation of space has a significant impact on occupant well-being. While addressing the issues of existing crowding and major repairs, both explored above, may reduce this need; additional housing must be developed as transitional or safe spaces for community members in particular need.

Future Growth

Meeting the four types of need studied in this report- existing need, growth related need, deterioration- related need and migration need-requires significant development of new housing. Rather than relying on standard plans of subdivision models of housing being developed across First Nations, community members were given the opportunity to vision solutions for their community. Visioning of community growth took place at two scales: individual houses and community. Using both survey questions and workshop activities specifically designed for Nibinamik, community member values, goals and aspirations for the future were recorded.

Community Planning

Building Community through Shared Spaces

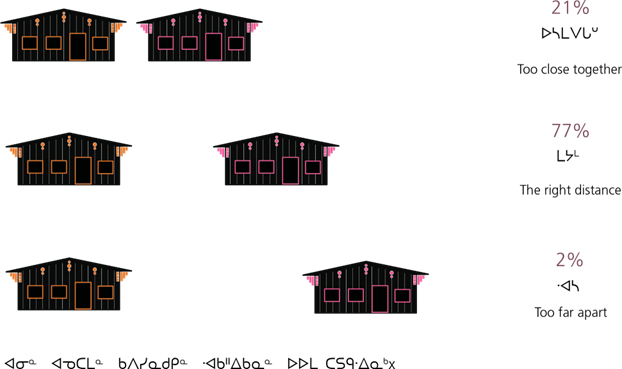

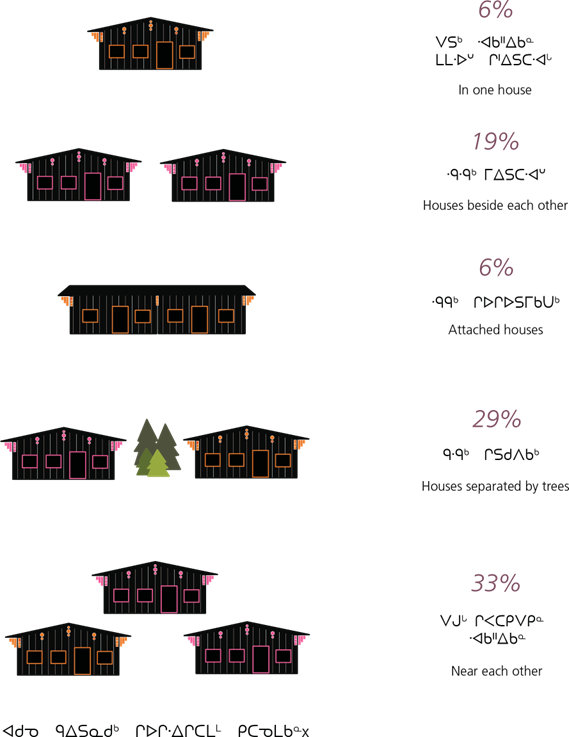

Standardized models of subdivision commonly used for new community development in the south and exported across First Nations in Canada emphasize private space, and most often do not consider how the existing landscape can enhance the housing development. The survey found that 77 percent of community members feel that houses are well spaced; the distance between houses does not feel too crowded. The absence of utilizing existing natural features within these housing models minimizes potential for shared spaces for community members- the private lot becomes emphasized and reduces opportunities for paths and interaction between houses. Nonlinear development opportunities were explored in workshops and looked at alternatives to the suburban grid style of housing. Alternatives focused on increasing public spaces and maintaining the natural environment.

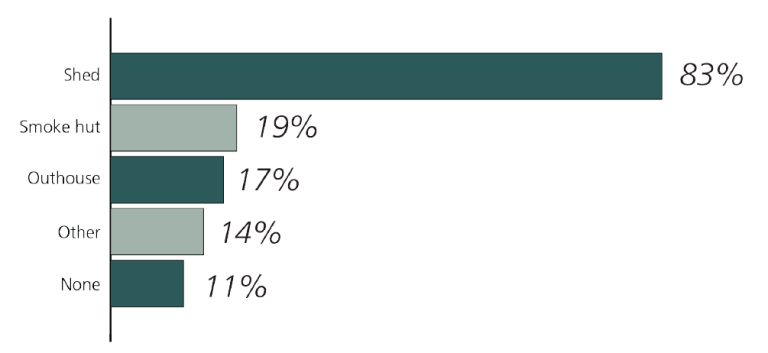

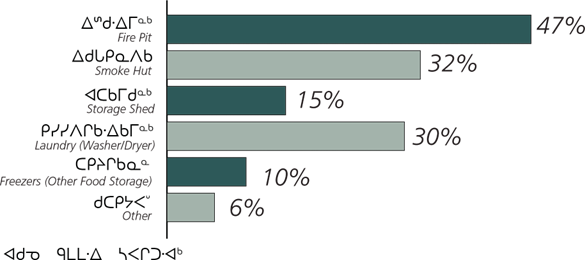

Community members expressed the desire for more shared spaces. Shared spaces within the home, such as the living room and kitchen, were ranked as the most important spaces in the home as these areas allow for interaction and togetherness. This desire for spending time with others extends beyond the house to the wider community. 47 percent would of community members expressed that they would share a fire pit, 32 percent would share a smoke hut, and 30 percent would share laundry facilities. These opportunities to build community and opportunities for social gathering may be best leveraged through a housing plan that organically blends with the natural environment in an effort to take advantage of natural features. This would allow for smaller gathering spaces between neighbours.

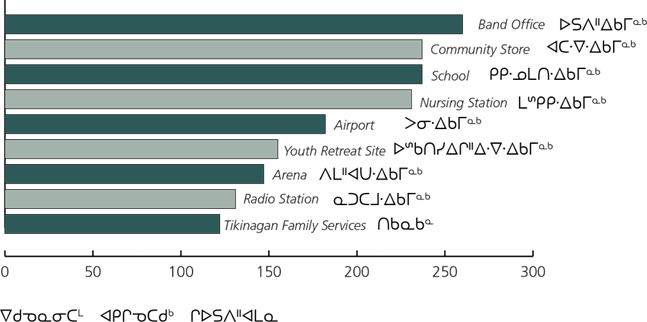

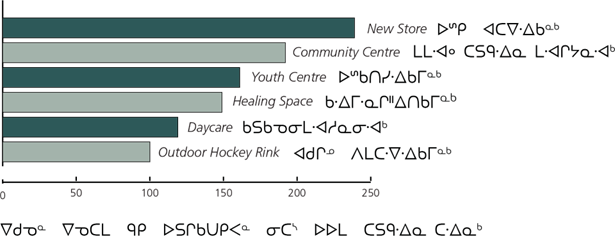

Community Facilities

The Band Office was ranked as the most important community facility, followed closely by the store and school. These facilities each have distinct important roles but, are also places of interaction and gathering. Top choices for new community facilities were a new store, community centre and youth centre. These shared spaces point to a desire for places community members can meet and gather, outside of their home.

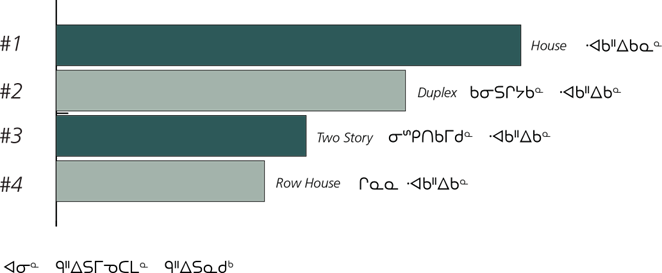

Housing Typology

While there is a strong desire for shared spaces within the community they must be balanced with a need for privacy. 83 percent of people ranked having a detached house as their preference, with only 17 percent preferring a duplex. However, not all neighbours are viewed equally. Community members demonstrated in their willingness to share features, that if their neighbours were family members they would be much more likely to share storage and recreational structures. This is further supported by 43 percent of community members expressing that it was either important or very important that they live nearby family. These important ties of family and kinship can play an important role in establishing the balance of shared and private spaces.

Solutions for Community Housing Need

The following pages explore different types of housing need identified through the survey and offers projections and scenarios which look to meet the recorded need. However, need can only truly be addressed through local decision making and solutions. Throughout this project, we have looked to record and learn from the experiences of community members to understand how the housing system – built form, design, governance and management- can more appropriately address the needs of Nibinamik’s community members. These solutions will continue to evolve and change, and yet the housing system can continue to honour the traditions and spirit with which the community was established.

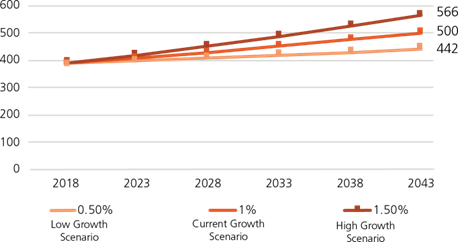

Here, we explore four types of need identified: existing need, growth-related need, deterioration-related need, and return to community need. Using the average, annual growth rate of the last 25 years of 1 percent to project 25 years into the future, we forecast an on-reserve population of 500 in 2043. Growth related need and housing development must exist within the context of meeting other community needs. Housing developed must be guided by specific community climactic, geographic and cultural needs. The following looks to guide decision-making in conjunction with the above findings.

Existing Need

The first type of need discussed is existing need. Three different methods were used to quantify existing need: number of bedrooms identified by community members needed to address crowding; number of houses needed to address family doubling; and the existing waiting list for housing as of 2016. Existing need only includes off reserve members looking to return in the final measure, and this measure may under-count them, it also does not include replacement need from deteriorated housing stock.

Growth-Related Need

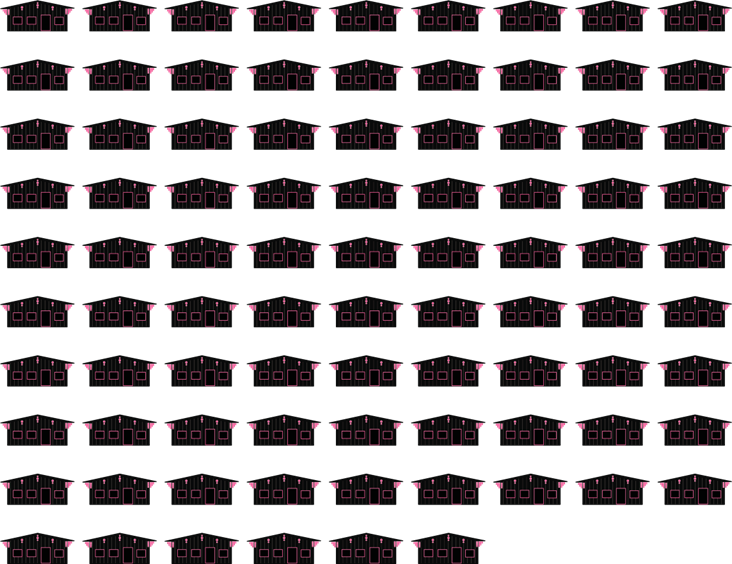

Below, we explore four scenarios that demonstrate different ways in which housing need can be projected and its impact on the built environment. Importantly, these scenarios focus exclusively on housing and not the required community development and infrastructure needs associated with such housing growth. While this project touched on design options for community growth, definitive answers are outside the scope as are different servicing options. The presented scenarios offer examples of possible need projections and solutions and should not be seen as prescriptive, but instead as guiding in creating community-based solutions.

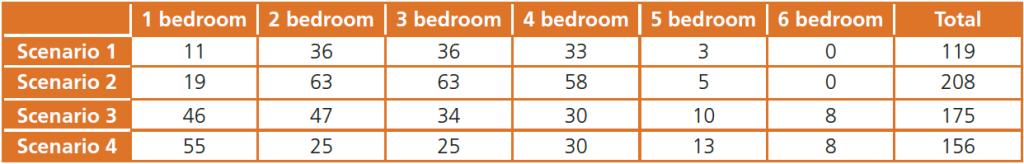

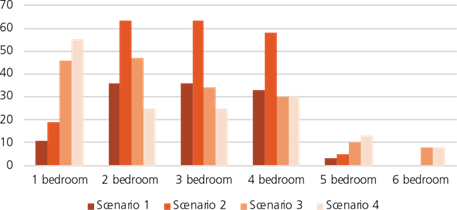

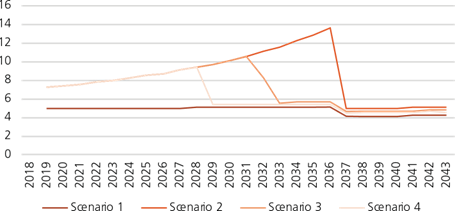

Scenarios

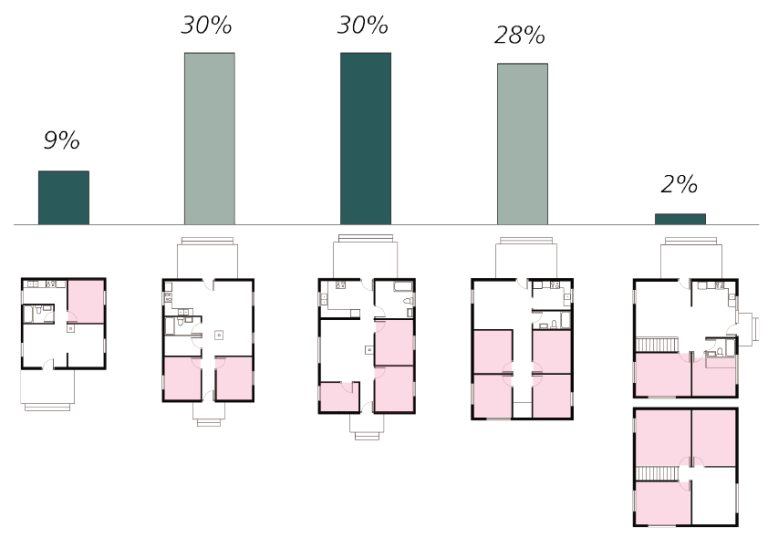

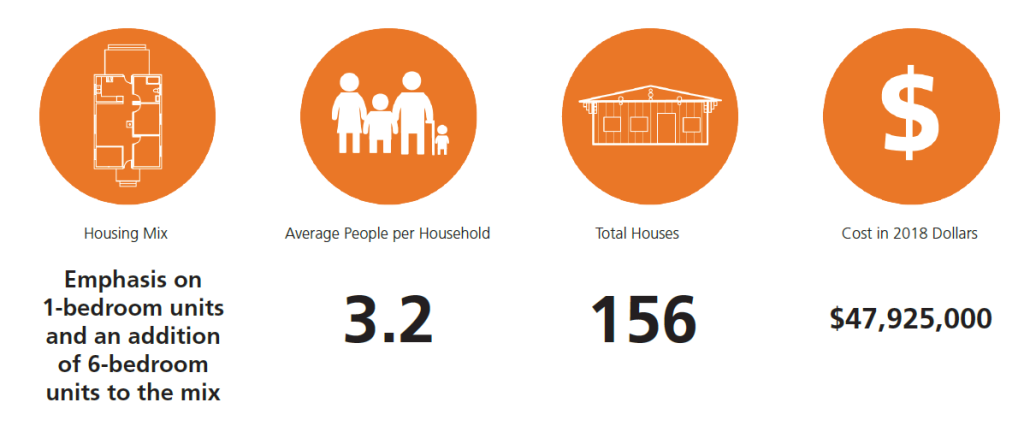

The scenarios below are designed to accommodate the projected population of 500 by year 2043. While each scenario accommodates the same population, objectives and corresponding housing mix changes for each. The first scenario projects need into the future using current density and unit mix. The second scenario projects need with the goal of decreasing household density, thereby decreasing crowding in the community. Scenario 3 is modeled on current and projected household composition. Lastly, Scenario 4 is projected to meet declining density within the house while emphasizing 1-bedroom units with the addition of 6-bedroom units to the mix.

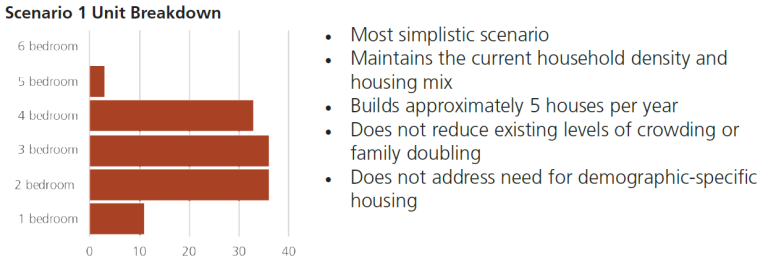

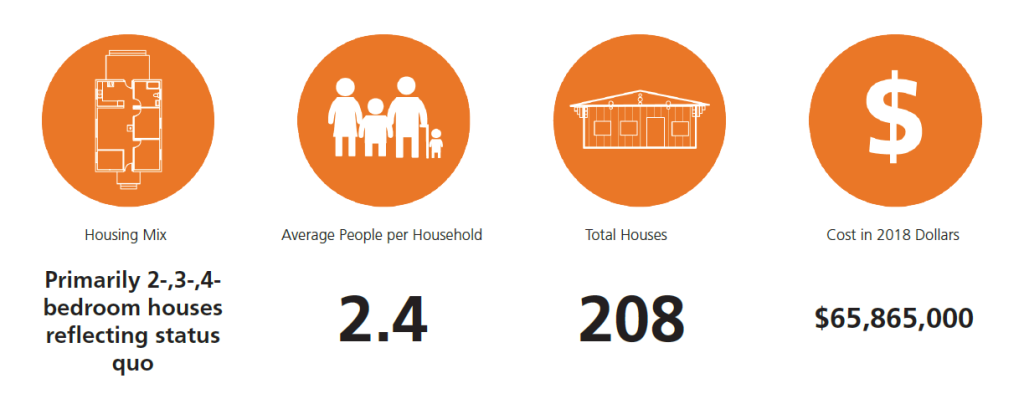

Scenario 1: Status Quo

Scenario 1 projects housing need based off the current average household density and housing mix. In this scenario an average of five houses are planned to be built per year, resulting in a total of 119 houses in Nibinamik in 25 years. While this scenario allows for community growth there are limitations realizing housing’s role in creating community well-being. Scenario 1 models need based on current household density thereby overlooking crowding issues. As a result, this scenario does not allow for a reduction of existing levels of crowding or elimination of family doubling. While there is a range of housing mix- primarily 2-, 3-, and 4-bedroom houses- there is limited consideration of demographic-specific housing. The equal ratio of these unit types does not consider existing family structures or needs of youth, single adults, Elders, or those who wish to live in multigenerational family households. The persistence of crowding in this scenario will create further issues with safety and well-being. While this model provides a simple way to project housing need, it does not change the housing system nor adapt to the unique needs and preferences of Nibinamik.

Highlights:

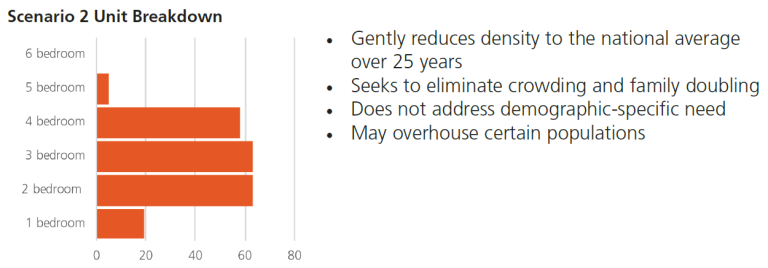

Scenario 2: Decreasing Density

Scenario 2 strongly resembles Scenario 1 with the exception of household density. The purpose of Scenario 2 is to reduce average household density in an effort to reduce crowding in Nibinamik. This scenario projects a need for 208 total houses in the community within 25 years. Reducing density is a simple approach to addressing Nibinamik community members greatest wellness concern with regards to housing, crowding and unwanted family doubling. Reducing density incrementally over 25 years to a target of 2.4 people per household would put Nibinamik on par with the current average Canadian household. Scenario 2 continues to replicate Nibinamik’s existing housing mix, with a focus on 2-, 3- and 4-bedroom units. While it does not address demographic-specific need, the total number of houses is greatly increased to meet to both existing and future need.

Highlights:

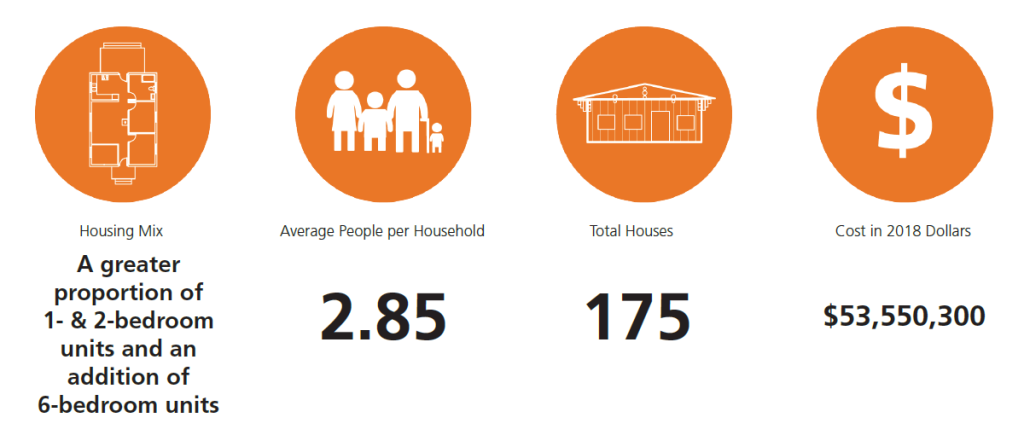

Scenario 3: Household Composition and Decreasing Density

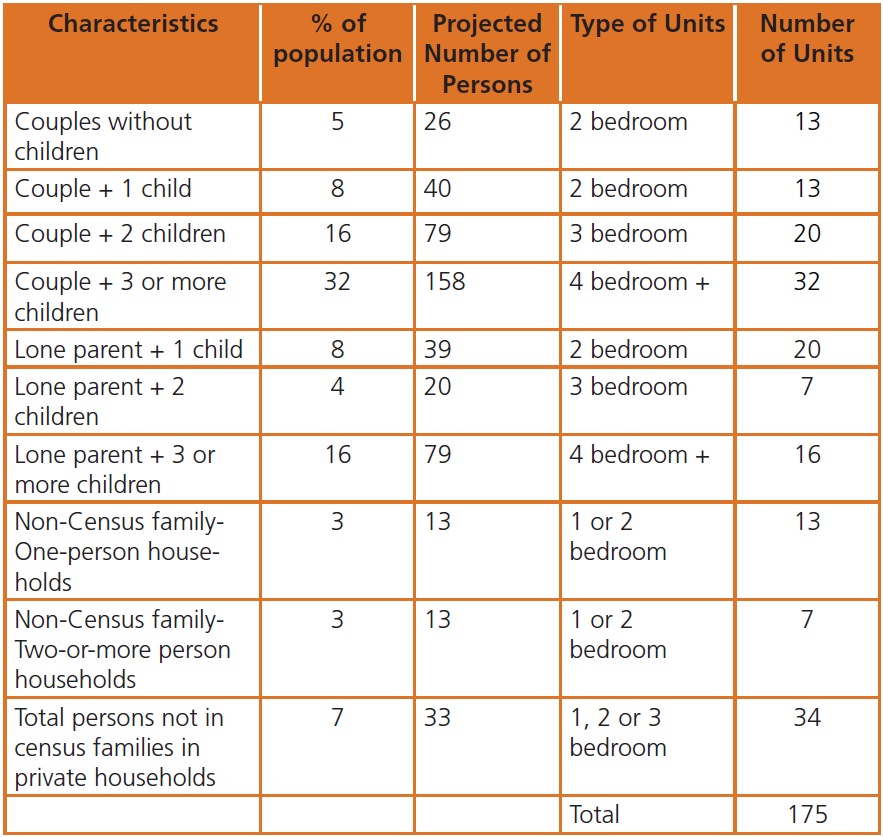

Scenario 3 uses current household composition and family characteristics from Census 2016 to determine the projected need of units to year 2043. Projections considered parent(s) with children, couples without children, non- census-family households and persons not in census families in private households. Scenario 3 seeks to create a housing mix aligned to the life stages of community members by matching household composition to housing typology. Using an approach based on National Occupancy Standard, each projected household is placed in a home with sufficient bedrooms to eliminate crowding, and the needs of singles are met. However, this model is biased towards a southern conceptualization of private, family space and thus only includes limited options for families to desire to live in multi-generational or multi-family households or who may have alternative understandings of households and families from Census categories.

Highlights:

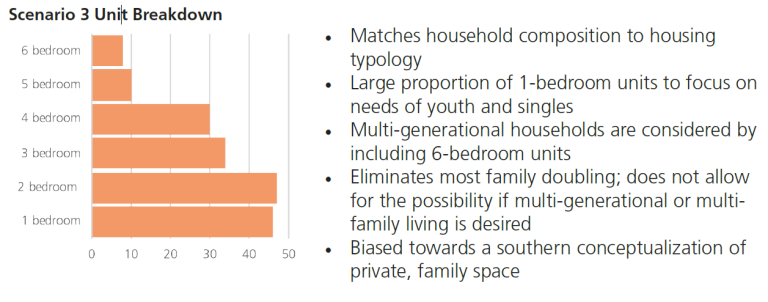

Scenario 4: Singles and Decreasing Density

Scenario 4 identifies singles and youth as a demographic currently experiencing higher levels of housing need and homelessness. Youth and singles both currently struggle to obtain housing with families given priority for new or available units. Unable to obtain housing of their own, singles often live in situations of family doubling forced to stay with a relatives. In this scenario, the 25 percent of single and without children community members are housed in one- and two-bedroom units specifically designed for their situation. Projected into 2043 this population will total 125.

Additionally, Scenario 4 adds 5- and 6-bedroom units, reflecting some community members’ desire to live in multigenerational or multi-family homes. These larger home and family sizes contribute to a slightly higher density in this scenario than the previous two, but reflects the diversity of household structures desired by community members.

Highlights:

Deterioration-Related Need

Currently, there are 93 houses in Nibinamik. However, given the existing level of repairs needed and the short lifespan of houses it is assumed that all existing houses will need to be replaced over the next 25 years. Short replacement times and rapid deterioration are seen across fly-in First Nations and are large contributors to persistent housing need.31 Shorter lifespan of houses have been attributed to: climatic inappropriateness, geographic inappropriateness, poor quality of materials and labour and lack of a sense of ownership.

Within Nibinamik a high level of deterioration-related need is already present. Need for major repairs in the community, demonstrated above, are well above national averages. This high level of need is ongoing, and adds to the housing need already existent in the community. Replacement, rather than ongoing band-aid repair solutions, can look to address some of the systemic problems harming the existing housing stock.

Return to Community

In the survey, 91 percent of community members expressed they would choose to locate their house within the current community and only 2 percent would move to the city. This overwhelming response to staying in the community confirms the strong connection community members have to Nibinamik and its surrounding environment. This connection extends outside the community to members who currently live in a city. At present there are 134 registered band members living outside of Nibinamik. In the survey, 59 percent of community members noted that they have family members who live in a city that would like to return to Nibinamik. Although there are many factors that could cause community members to locate in the city- such as employment, schooling and healthcare- one reason that limits the opportunity to return is a lack of housing to accommodate this need. For Nibinamik to grow and be a place that everyone can call home, housing solutions will need to account for this need.

As Nibinamik has already started its path towards holistic community wellness, positive community change may encourage more community remembers to return home. Changing issues of economic development, education, housing, infrastructure and other issues of wellness specifically address many of the reasons identified by the 59 percent of community who spoke of their family members living away from the community. Improving holistic community well-being will likely increase demand for housing and result in elevated need and need.

59 percent of respondents said they currently have family members living in the city who hope to move back to Nibinamik.

Recommendations

All four types of housing need must be addressed

Four forms of housing need have been identified in Nibinamik: existing need, growth-related need, deterioration-related need and migration-related need. The four types of need reveal the full scope and complexity of the housing shortage in Nibinamik. Existing- and deterioration-related need demonstrates the housing shortfall affecting Nibinamik members currently living in community. Migration- and growth- related needs reveal internal and external pressures and shortage of housing due to community growth. Addressing only a single form of housing need contributes to the ongoing homelessness experienced by some community members.

Housing need requires immediate action

The four types of housing need reveal the homelessness being experienced by Nibinamik community members. Housing need will continue to grow and compound unless appropriate housing solutions are enacted. Each day, the safety and security of community members is impacted by the existing inequitable housing outcomes. Improvements in the well-being of all community members will only occur through immediate action.

Housing must support individual pride and control in living environments

Housing need is not simply an issue of shelter but is an issue of individual and community pride and well- being. A continued lack of safe and quality housing impacts the mental, physical and spiritual well-being of community members. Improving housing conditions through community-led design and community- created management systems (i.e. housing policy) can contribute to a greater sense of individual and community pride as well as support Nibinamik’s self-determination.

Nibinamik is a unique place that requires unique attention in design and materiality- standardization won’t do

Housing self-determination must be supported at all points of Nibinamik’s housing system. From policy to design, community-based solutions are required to support individual and community well-being. Nibinamik’s history shows the importance of community-led design and construction of housing. Unique, community led solutions, created by Nibinamik community members must be supported by all levels of government and community partners.

Endnotes

1. Stewart Clatworthy, “Housing Needs in First Nations Communities,” Canadian Issues 29 no.2 (2009): 19-24.

2. Nibinamik First Nation, “Land Use Plan”, 1987.

3. See Note 2.

4. Canada. Statistics Canada, “Summer Beaver, S-É [Census subdivision], Ontario and Kenora, DIS [Census division], Ontario (table).” (Census Profile, 2016 Census. Statistics Canada, Catalogue no. 98-316-X2016001, Ottawa, Released November 29, 2017). Last modified April 24, 2018. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/ page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=CSD&Code1=3560086&Geo2=CD&Code2=3560&Data=Count&SearchText=summer%20 beaver&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&TABID=1

5. Canada. Canadian Housing and Mortgage Corporation, “What is Core Housing Need?” last modified March 23, 2016. https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/en/hoficlincl/observer/observer_044.cfm

6. Stewart Clatworthy, “Housing Needs in First Nations Communities,” Canadian Issues 29 no.2 (2009): 19-24.

7. Canada. Statistics Canada, “Canada [Country] and Canada [Country] (table).” (Census Profile, 2016 Census. Statistics Canada, Catalogue no. 98-316-X2016001, Ottawa, Released November 29, 2017. Last modified April 24, 2018. https:// www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E

8. Hayward, Geoffrey D. “Home as an Environmental and Psychological Concept,” Landscape 12 (1975): 2-9.

9. Judith Sixsmith, “The Meaning of Home: An exploration study of environmental experience,” Journal of Environmental Psychology 15 (1986): 191-210.

10. Sandy G. Smith, “The Essential Qualities of a Home,” Journal of Environmental Psychology 6 (1994): 281-98.

11. Nibinamik First Nation, “Nibinamik First Nation Community Wellness Index”, forthcoming.

12. Human Rights Education Associates, “The Right to Housing,” 2003.

13. Canada. Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples, “Housing on First Nations Reserves: Challenges and Successes” (Senate Canada, 2d sess., 41st Parliament, 2015).

14. See Note 4.

15. Canada. Statistics Canada, “2001 Canadian Census Tables.” (Using CHASS (distributor)). http://dc1.chass.utoronto. ca.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/census/2001_rp_all.html (accessed April 7, 2018).

16. See Note 4 & 7.

17. Canada. Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples, “On-Reserve Housing and Infrastructure: Recommendations for change” (Senate Canada, 2d sess., 41st Parliament, 2015).

18. Canada. Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples, “Housing on First Nations Reserves: Challenges and Successes” (Senate Canada, 2d sess., 41st Parliament, 2015).

19. Maria Amérigo and Juan I. Aragonés, “A Theoretical and Methodological Approach to the Study of Residential Satisfaction,” Journal of Environmental Psychology, 17 (1997): 45-57.

20. Amos Rapoport, Human Aspects of Urban Form, (Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press, 1977).

21. Amos Rapoport, House Form and Culture, (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1969).

22. Juan I. Aragonés, “The Dwelling as Place: Behaviors and Symbolism,” in Residential Environments: Choice, satisfaction, and behavior, edited by Juan A. Aragonés, Guido Francescato and Tommy Gärling (Westport, Connecticut: Begin & Garvey, 2002), p. 163-182.

23. David Canter and Cheryl Kenny, “Approaches to Environmental Evaluation: An introduction,” International Review of Applied Psychology 31, (1982): 145-151.

24. Wolfgang F.E. Preiser, Harvey Z. Rabinowitz, and Edward T. White, Post-Occupancy Evaluation (New York, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company Inc, 1988).

25. James R. Anderson, Guido Francescato, and Sue Weidmann, “Evaluating the Built Environment From the User’s Point of View: An attitudinal model of residential satisfaction,” in Building Evaluation, edited by Wolfgang F.E Preiser (New York, New York: Plenum Press, 1989), p. 181-198.

26. Wolfgang F.E. Preiser, Harvey Z. Rabinowitz, and Edward T. White, Post-Occupancy Evaluation (New York, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company Inc, 1988).

27. See Note 5.

28. National Collaborating Centre For Aboriginal Health, “Housing as a Social Determinant of First Nations, Inuit and Métis Health,” 2017. https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/determinants/FS-Housing-SDOH2017-EN.pdf

29. John Fien, Esther Charlesworth, Gini Lee, David Morris, Doug Baker and Tammy Grice, “Flexible Guidelines for the Design of Remote Indigenous Community Housing,” AHURI Positioning Paper No. 98 (2007).

30. Irwin Altman and Martin M. Chemers, Culture and Environment (Belmont, California: Wadsworth Inc.), 1980.

31. Assembly of First Nations, “Fact Sheet – First Nations Housing On-Reserve” 2013. https://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/ housing/factsheet-housing.pdf

References

Altman, Irwin. and Martin M. Chemers. Culture and Environment. Belmont, California: Wadsworth Inc., 1980. Amérigo, Maria, and Juan I. Aragonés, Juan. ”A Theoretical and Methodological Approach to the Study of Residential

Satisfaction.” Journal of Environmental Psychology, 17 (1997): 45-57.

Anderson, James R., Guido Francescato, and Sue Weidmann. “Evaluating the Built Environment From the User’s Point of View: An attitudinal model of residential satisfaction.” In Building Evaluation, edited by Wolfgang F.E Preiser, p. 181-198. New York, New York: Plenum Press, 1989.

Aragonés, Juan I, “The Dwelling as Place: Behaviors and Symbolism.” In Residential Environments: Choise, satisfaction, and behavior, edited by Juan A. Aragonés, Guido Francescato and Tommy Gärling, p. 163-182. Westport, Connecticut: Begin & Garvey, 2002.

Aragonés, Juan. I., Guido Francescasto, and Tommy Gärling. “Evaluating Residential Environments.” In Residential Environments: Choise, satisfaction, and behavior, edited by Juan A. Aragonés, Guido Francescato & Tommy Gärling, p. 1-14. Westport Connecticut: Begin & Garvey, 2002.

Assembly of First Nations. “Fact Sheet – First Nations Housing On-Reserve” 2013. https://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/housing/ factsheet-housing.pdf

Canada. Statistics Canada. (n.d.) 2001 Canadian Census Tables (table). Using CHASS (distributor). Version updated n.d. http:// dc1.chass.utoronto.ca.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/census/2001_rp_all.html (accessed April 7, 2018).

Canada. Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples. “Housing on First Nations Reserves: Challenges and Successes.” Senate Canada, 2d sess., 41st Parliament, 2015.

Canada. Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples. “On-Reserve Housing and Infrastructure: Recommendations for change.” Senate Canada, 2d sess., 41st Parliament, 2015.

Canada. Canadian Housing and Mortgage Corporation. “What is Core Housing Need?” Last modified March 23, 2016. https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/en/ hoficlincl/observer/observer_044.cfm

Canada. Statistics Canada. (2017). “Summer Beaver, S-É [Census subdivision], Ontario and Kenora, DIS [Census division], Ontario (table)”. Census Profile. 2016 Census. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-316-X2016001, Ottawa, Released November 29, 2017. Last modified April 24, 2018.

https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E

Canter, David and Cheryl Kenny. “Approaches to Environmental Evaluation: An introduction.” International Review of Applied Psychology 31, (1982): 145- 151.

Clatworthy, Stewart. “Housing Needs in First Nations Communities.” Canadian Issues 29 no.2 (2009): 19-24.

Fien, John, Esther Charlesworth, Gini Lee, David Morris, Doug Baker and Tammy Grice. “Flexible Guidelines for the Design of Remote Indigenous Community Housing.” AHURI Positioning Paper No. 98 (2007).

Hayward, Geoffrey D. “Home as an Environmental and Psychological Concept.” Landscape 12 (1975): 2-9. Human Rights Education Associates. “The Right to Housing”. 2003.

National Collaborating Centre For Aboriginal Health. “Housing as a Social Determinant of First Nations, Inuit and Métis Health.” 2017. https://www.ccnsa- nccah.ca/docs/determinants/FS-Housing-SDOH2017-EN.pdf

Nibinamik First Nation. “Nibinamik FIrst Nation Community Wellness Index.” forthcoming. Nibinamik First Nation. “Land Use Plan.” 1987.

Preiser, Wolfgang F. E., Harvey Z. Rabinowitz, and Edward T. White. Post-Occupancy Evaluation. New York, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company Inc, 1988.

Rapoport, A. (1969). House Form and Culture. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. Rapoport, A. (1977). Human Aspects of Urban Form. Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press.

Sixsmith, Judith. “The Meaning of Home: An exploration study of environmental experience.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 15 (1986): 191-210.

Smith, Sandy G. “The Essential Qualities of a Home.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 6 (1994): 281-98.

Appendices

Appendix A: Methodology

The Nibinamik Housing Survey was undertaken over two years between October 2016 and February 2018. The survey was designed in two parts – a household survey and an individual survey which could be completed by multiple household members. By dividing the survey into two parts one per household and one for all community members duplicates were avoided for physical counts of bedrooms and common issues.

Surveys were administered by Housing Committee members and housing staff, together design lab and +city lab. Surveys were conducted in person to reduce language and literacy barriers and allow for questions to be clarified and extra notes to be taken. The individual portion of the survey was translated by a community member into Oji- Cree syllabics in order to administer the survey to a greater number of community members.

Surveys were transcribed at the end of the surveying process. All responses were entered into an excel sheet following a data entry guide. Qualitative, written responses and notes, were entered as they were written maintaining spelling and grammar of respondents. Closed question responses were coded. Qualitative responses were reviewed for content and then coded. Recurring words were highlighted and used as a basis for coding and organizing responses.

Workshops

Community workshops were held to supplement survey information by allowing for more in depth discussion of design, community growth and governance questions. Workshops were held with youth, Elders and the

community. School workshops were coordinated with the staff and teachers ahead of time and Elders’ workshops were coordinated through NAME. Community wide workshops were advertised through social media, radio and flyers to ensure all community members notified. During workshops community facilitators and translators were present.

Census Data

2016 Census data for household characteristics and household dwelling characteristics was collected to calculate averages for Nibinamik, Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN) and Canada. Data for 5 communities – Beaverhouse First Nation, Hornepayne First Nation, Mocreebec Council of the Cree Nation, Koocheching First Nation and Whitewater Lake First Nation- were not available for calculating NAN housing statistics.

Census data from 1996, 2006 and 2016 were collected for population pyramids and age cohorts. Cohort data from census 2001 and 2011 is not available for Nibinamik.

Data for population projections are derived from Census data sections from 1991 and 2016. Th average growth rate of 1% was calculated by determining the population change between 1991 and 2016 and dividing by

25 years. A low and high growth rate were calculated +/- 0.5 percent from the calculated growth rate of 2.9 percent to illustrate the range of future populations growth. Population data from INAC’s Socio-Economic and Demographic Statistics showed large variations in population sizes and could not be used.

Appendix B: Future Housing Scenario Assumption

A series of assumptions were used to create future housing scenarios. These assumptions need to be taken into consideration when evaluating each scenario. Each scenario used the same population projection of 1% growth rate based on average annual growth rate. The population is projected to be 500 by 2043.

Scenario 1

- The number of future houses needed was determined by using the current housing density (people per household) and was projected into the future to show the status quo.

- The housing mix was determined by using the current mix of housing. Data on the current mix was taken from the surveys instead of census data because the housing survey had a larger sample size (47% sample size compared to census 25% sample size).

Scenario 2

- Scenario 2 focused on a gradual reduction of housing density to 4 to reach the current national level of people per household and stabilized at 2.4 for the remainder of the projection period.

- Housing mix was determined using the same method as Scenario 1

Scenario 3

- Current household structure and family characteristics from the 2016 Census were used to determine housing mix and the number of houses needed.

- It is assumed that total persons not in census families in private households may opt to live on their own if housing is available and are partially distributed among different unit types.

- The target housing density is determined by number of houses needed divided by 2043 population projection.

Scenario 4

- Scenario 4 is based on the current proportion of individuals not married or in common law and have no children (25%).

- The density target is a gradual decrease of 1 person from current household density to 2 and stabilizing over the remaining 25-year period.

- The housing target of 156 is determined by the target density of 3.2 divided by 2043 population projection.